In 2021 the term “rural healthcare” lies in a politically correct universe somewhere between pariah and relic. Phrases like “outstate” or “Greater Minnesota” are now considered more appropriate for almost anywhere outside the Metro areas, and smaller communities are homes to top quality, cutting edge health care facilities. Perhaps the term “rural” evokes unintended comparison to Mayberry R.F.D., but in reality, 97% of today’s U.S. geography — nearly a quarter of the U.S. population — falls under rural healthcare delivery. With the population spread out over a wide land area, the geography of rural America makes access to healthcare a prominent challenge.

To address the issue, we dissect four areas that can be improved with innovation in architectural design: population, place, professionals, and pathways. With special consideration of facility design needs and community-based research, we can all work to transform the term “rural healthcare” to be perceived in a more positive light. With efficient pre-planning and collaborated design, architecture firms have the tools to execute solutions to more efficiently accommodate traveling patients, assist in workforce retention, pinpoint closer-proximity access areas, and address privacy and remote care.

Population

Chronic health conditions are one of the most influential determinants of health status, and rural populations tend to see a higher incidence of these risk factors. Obesity, heart disease, diabetes, and addiction, are more common without access to regular, individualized healthcare. It is not surprising that chronic health conditions are more common in rural areas. The culture behind a community also heavily impacts the health of its people. Patients in rural communities are 1.7 times more likely to avoid healthcare visits than their urban counterparts. Rural culture is derived from generations of “self-care” — believing themselves to be “more hearty”.

Privacy is major challenge in avoidance of healthcare as many rural patients are all too familiar with the doctors, nurses, and other patients in the healthcare setting. This is most commonly seen in the area of mental health. Rural residents are less likely to participate in their healthcare system due to the perceived “neighbor” stigma. To create a new perception, we need to start with a well-planned design that can guide the patient’s journey more discreetly, from parking, to check-in, and waiting area. These areas can be reconfigured for less patient-to-patient visuals and heightened acoustic privacy.

In some cases, virtual or kiosk check-in stations, along with patient self-rooming, have been useful in maximizing privacy and patient distance. In Moorhead, Minnesota’s Sanford Clinic, JLG Architects designed for the option of both a patient concierge, as well as an electronic kiosk which assigns patients a Real-Time Locating System tag for self-rooming. The staff is available to direct the patient to their exam room, and intuitive wayfinding is used within the building’s interior design through color-coded bulkheads and carpet tiles. In addition, each exam room is equipped with a scale and blood pressure monitoring to take patient vitals in the privacy of their exam room. This is simply a collaborative, onstage-offstage care delivery model that makes clinic visits more efficient for the providers and less threatening for the patient.

Sound insulation is also necessary in partitions around consultation rooms and telemental health space to prevent confidential conversations from traveling beyond the room. In a scenario that relies on common areas with open workstations, it’s crucial to designate private clinical office space as well. Acoustically-sound consultation rooms or conference rooms can be used to meet this need

Professional

Among rural America’s challenges, the greatest is access to healthcare staff. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services uses a metric and tool set to address access to medical, dental and mental health services called Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). According to the American Hospital Association, two-thirds of the nation’s HPSAs are located within rural areas. Rural healthcare systems face two issues related to staffing: not enough money to bring on more staff, and not enough staff interested in working for their systems. Healthcare is already following a trend of ultra-specialization by providers. This has resulted in fewer general practitioners, and a heightened expectation of doctor specialization by patients. To maintain health in rural populations and workforce will require new and emerging partnerships. These will include more involvement and investment by community city councils and local industry.

To address long-term employee retention, we consider post-pandemic stress levels in the wake of staff shortages, paying close attention to the toll of losing fellow co-workers and patients. This is an important catalyst in the conversation of why many healthcare environments need modernizing. Prioritizing staff well-being is a goal we are seeing across the board in architectural design, but even more so in healthcare. In high-stress environments, it’s important that design incorporates natural light, respite spaces, quiet meditation rooms, larger outdoor spaces, and access to walking paths.

Design firms can collaboratively work to include a wide range of calming work areas such as “huddle” spaces for informal team collaboration, as well quiet workspaces that include acoustic detailing and technology that supports auditory privacy. An effective design also integrates a modular planning approach that can support future rearrangement and changes in staffing and workflow.

Technology limitations in rural healthcare settings is another area to be addressed. Advancing instrumentation and software can be pivotal in recruiting and retaining existing staff, while helping reduce automated, day-to-day tasks. Additionally, post-lockdown, we look at empty office spaces from departments that have been successful working remotely. These office spaces can be effectively redesigned as virtual telehealth offices or private consultation rooms.

Place

Rural populations often require travel for specialized healthcare services, and, as a result, are looking for a one-stop-shop approach when they arrive. Ideally, they need a campus or clinic designed with an integrated model of care where they can easily navigate between all appointments in a single trip. The current push for decentralized community care and reducing the number of steps between appointments is only the beginning. Ambulatory care centers with expanded outpatient care are creating new options that gravitate away from the hospital into smaller, freestanding medical office buildings that include amenities such as retail, coffee shops, and fitness.

Moorhead’s Sanford Clinic is a prime example as it’s optimally located to serve both the Fargo-Moorhead community and surrounding rural areas. Because of the nature of the location, the 49,250 square-foot clinic is extremely patient-focused, offering a wide range of services including a pharmacy, a large imaging suite, a full-service laboratory, and an area dedicated to occupational medicine. All of these services under one roof, combined with a medical home model, allows for ease of use and efficiency for all patients. Their team understood the impact of accessing multiple specialists and the way this model would positively affect their patients and healing process.

For rural healthcare systems that don’t have the luxury of a multiple-building campus or access to a wide variety of providers, “neighborhoods” within a single building provide individualized outpatient services without the sterile feel of a traditional hospital. Smaller communities can see big benefits with “coopetition,” individual practitioners sharing costs throughout a unified space. The loss of a larger retailer or grocery branch can offer cost efficient possibilities in terms of creating a new health care delivery center.

Pathways

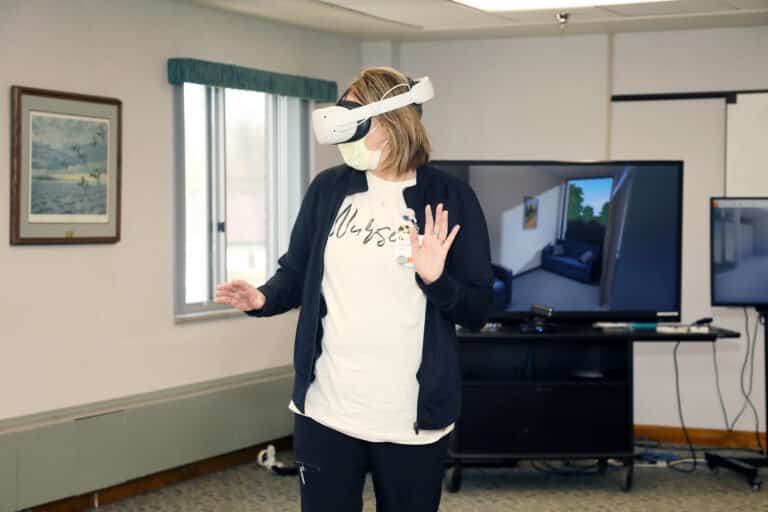

While advances in telehealth, wearables, and virtual hospitaling have propelled us through a pandemic, they’re also game changers for future-proofing rural healthcare. In the past, rural hospitals sent patients out of the community for hospital-based or specialty services. Today, we can fast-track the ability to connect patients and providers for a more comfortable, “close to home” healthcare experience. This isn’t simply a matter of rural regions gaining better access to high-speed internet, the responsibility also lies with designers and practices to incorporate designated telehealth offices with integrated technology, privacy, lighting, acoustics, and a minimal, but soothing backdrop. This is a pandemic ripple effect that the industry must emphatically embrace.

Part of this embrace must be the continued investment from third party payers in reimbursement for telehealth services at rates similar to those for providing in-person care. Federal oversight, relaxed guidelines, and CMS pandemic response helped drive the initial telehealth boom and local payers fell in line. As data continues to grow supporting the efficacy and value of telehealth, particularly in rural communities, these new tools must be utilized in ways that are fair to providers and patients. It is important for telehealth to remain in the hands of local providers and not turned into another avenue of narrow networks, restricted access, and non-transparent pricing. New ways of measuring quality in telehealth care are emerging, as are ways of protecting the public from malpractice through telehealth. It is vital for physicians and health plans to be involved with these developments.

Health plans are also taking steps to help rural practices transition to a value-based reimbursement model that pays more for keeping patients healthier than using the old fee-for-service volume-based model. By providing both practice support and technology, new care coordination programs are helping to specifically address the problems of multiple chronic conditions that are so common in rural healthcare.

Beyond the building

Architects and designers have a growing responsibility in addressing healthcare delivery, research, and equity. With post-pandemic rural communities in a state of change, one of the most important pieces is to start looking at the data from the heart of the pandemic. Rural communities are going to be different, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Unfortunately, the quantitative data that is currently available is extremely outdated. It is crucial to create new methods of collecting data to help better advocate for the needs of the community. One such initiative is the UC Berkley Center for the Built Environment – a platform that offers robust tools for post-occupancy evaluations. They offer a deeply research-based approach with cutting edge exploration around how the built environment impacts human health, wellness, and resilience.

Redefining the role of the design professional to think “Beyond the Building” is increasingly valuable. Architectural firms need to serve healthcare clients outside of the brick and mortar and start setting the stage as strategic partners; partners who look at building great community connections.

In the architectural industry, a strong emphasis will also need to be placed on dignity, equity, and the positive impact of design to uplift humanity and community collectively. Design is a force for change. Earlier involvement for architects, designers, and community members in the design process will lead to more solution-sensitive concepts, ideas, and master plans. When design professionals are engaged at the forefront, they can effectively gather initial community input and use their expertise to lead to a well-rounded solution. Ideally, design involvement doesn’t end after project completion, but rather continues throughout post-occupancy evaluations to address improvements and future positive change.

When it comes to defining strategies for improving rural healthcare, we now have more informed pathways than ever before. By embracing innovation and elevating design partnerships, rural healthcare can respond positively to its many challenges and achieve unprecedented positive outcomes in overall population health, wellness, access, and research.

Todd Medd, AIA, is a Principal Architect, Healthcare Practice Studio Leader, and a passionate rural healthcare thought leader at JLG Architects.

Kristine Sallee, CID, LEED AP ID+C, WELL AP, EDAC and Evidence-Based Design Accredited Professional, is a Healthcare Designer and Client Relationship Manager at JLG Architects.