North Dakota tries to establish Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library

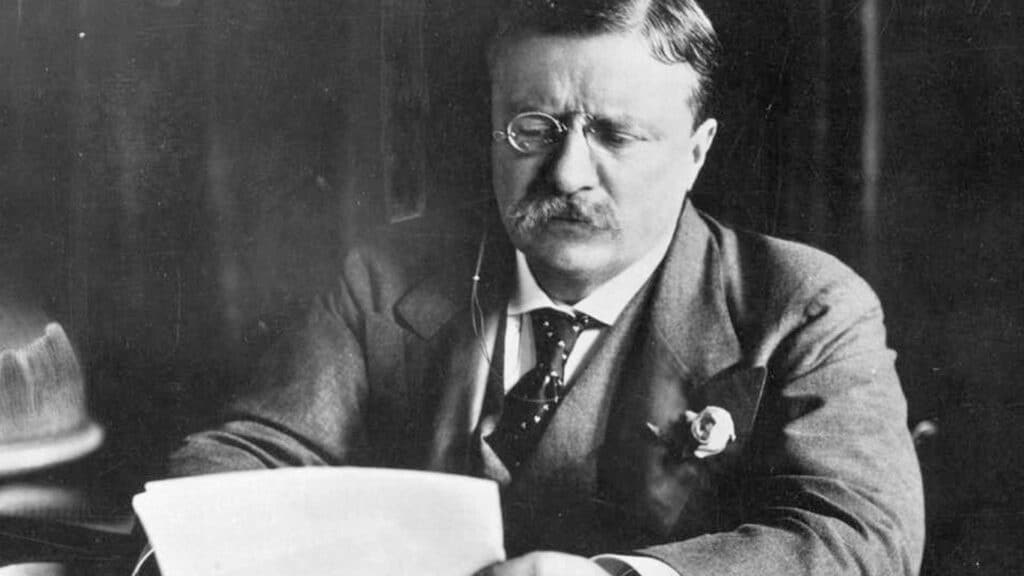

When Theodore Roosevelt came to Dakota Territory in 1883 to hunt bison, locals saw him as an Eastern tenderfoot with no clue on handling the hardships of frontier life. He turned adversity into adventure, later writing: “It was here that the romance of my life began.”

“I have always said I would not have been president had it not been for my experience in North Dakota,” wrote Roosevelt.

Now, enthusiasts of the 26th president are working to establish a Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in the North Dakota Badlands. They acknowledge it will be a challenge, but they’re working to raise millions, digitizing Roosevelt papers by the tens of thousands and promoting the majestic surroundings that Roosevelt so loved.

“The reason we put this library where we did, in western North Dakota, that’s the landscape that shaped and formed him into the Roosevelt we know,” said Clay Jenkinson, a leading Roosevelt scholar and re-enactor who is working as a consultant for the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation.

Roosevelt was a native of New York, where his birthplace and primary adult residence are national historic sites. But an effort a decade ago to establish a library there fizzled, and North Dakotans — who are eager to capitalize on ties to state natives such as baseball great Roger Maris, Western author Louis L’Amour and bandleader Lawrence Welk — saw an opportunity.

Roosevelt’s four years on a ranch in the North Dakota Badlands, when he was in his 20s, deepened his love for nature and made him a champion of wildlife conservation. He came to the area to recuperate from the deaths of his wife and mother on the same day. After his return to New York, he went on to serve as the state’s governor and the U.S. vice president before becoming president when William McKinley was assassinated in 1901.

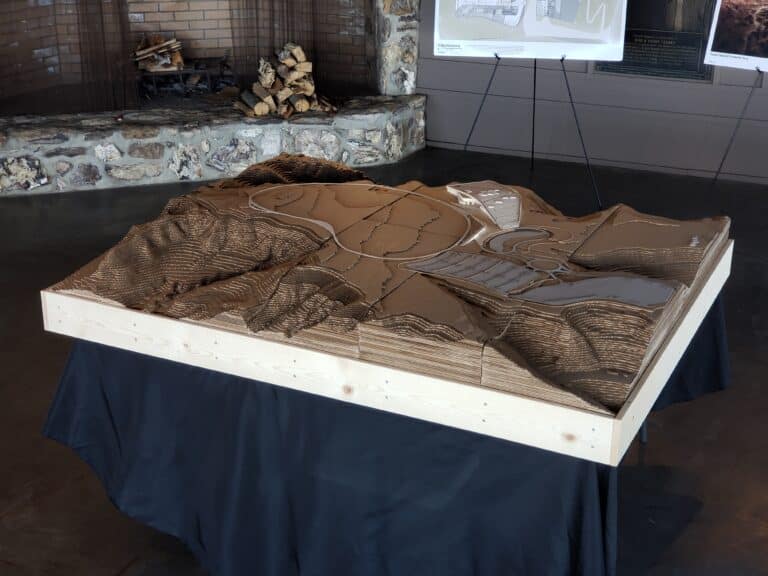

Roosevelt’s old turf in North Dakota is now a national park in his name — a rugged area of hills, ridges, buttes and bluffs where millions of years of erosion have exposed colorful sedimentary rock layers. The park is home to a wide variety of wildlife, from prairie dogs to wild horses and bison. It is North Dakota’s top tourist attraction, drawing more than 700,000 visitors annually.

The library is planned in Dickinson, with the museum about a half-hour drive away in Medora, a tourist town on the park’s doorstep.

The project has $15 million in hand from the state of North Dakota and city of Dickinson, which would like to capitalize on one of the most popular presidents who doesn’t already have a library. Organizers hope to raise another $85 million in private donations — a formidable challenge.

The Theodore Roosevelt Association, formed by Congress in 1920 to perpetuate Roosevelt’s legacy, is monitoring the fundraising effort.

“This is a very ambitious project and we want to make sure they have adequate funding, so we’re not backing something that turns out to be a half-done project,” said association CEO Tweed Roosevelt, Theodore’s great-grandson.

Source

Board decides on constructing Roosevelt Library in Dickinson, museum in Medora

The Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library is going to be built in Dickinson. Its museum, though, is going farther west to Medora in the Badlands.

The library foundation board, after a three-day meeting in Minneapolis decided its efforts would be divided between the two cities.

“My goal going into the meeting was to lead the board to a consensus and for us to have a clear vision of where we’re headed, and that’s exactly what happened today,” Bruce Pitts, Library Foundation Board of Trustees chair, said in a statement Friday, March 16. “Where we’re now headed is pursuing a grand vision for a museum and profound visitor experience in the Badlands, as well as pursuing the construction of a component in Dickinson that will support the work of the Theodore Roosevelt Center, as well as the scholars program at Dickinson State University.”

Shawn Kessel, Dickinson city administrator, applauded the decision Friday in a statement.

“The original concept of the TR Library was born out of a desire to improve facilities on the DSU campus. Today’s decision should fulfill that desire,” Kessel wrote. “Hats off to the board for dreaming big and striking out on an effort to provide a world class facility in North Dakota that will bring visitors from around the globe to Dickinson and western North Dakota.”

The decision ensures a permanent home at DSU for the digitization of Roosevelt’s writings, where the project began.

This project is estimated to cost roughly $146 million, with a $12.5 million appropriation from the City of Dickinson and the State of North Dakota.

Of the four scenarios considered by the board, dividing the effort between two cities was the only one that allowed for the state appropriation.

The Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum had begun its life as a digitization project at DSU, intended to convert the writings of Theodore Roosevelt to a digital archive and preserve them for posterity. That work is still ongoing, but the project has since grown to become a full blown presidential library project.

The project had been originally committed to be constructed wholly in Dickinson, and the city had offered financial support based on that commitment. Recently, it had been floated that Medora might be a better place to host the library — and it was made clear by the city that if the project left Dickinson, its financial support would leave the project. Should the city’s $3 million contribution have been withdrawn, a portion of Legislative appropriation would also have been withdrawn, and the project would lose out on around $15 million.

Splitting the project between two cities has advantages, according to documents provided by the Foundation:

Medora will provide for greater fundraising opportunities. The Foundation said its goal is to create an “iconic” experience there.

Construction on the Dickinson library is expected to start in November, with an opening date of November 2019.

At that time, the museum in Medora is expected to start construction, with an anticipated 2021 end date.

Presidential libraries are something of a modern phenomenon. The National Archives administers 14, starting with Herbert Hoover. By law, libraries for presidents before that have to be built without federal support.

Unlike the major libraries, a Roosevelt library wouldn’t have a trove of original documents because most already are in established collections. The Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University has digitized nearly 60,000 records, photographs, film clips and audio recordings.

The project would also include virtual exhibits and a full-scale re-creation of Roosevelt’s Elkhorn Ranch cabin, an 1,800-square foot cottonwood log structure hand-built by Roosevelt and his ranch hands.

“My biggest wish is to show the many sides of TR — the adventurer, the reformer, the naturalist, the soldier, the scholar, the family man, the list goes on and on,” said great-great grandson Kermit Roosevelt III, a University of Pennsylvania law professor.

Source

Work on Theodore Roosevelt library to start by end of the year

Work on the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in Dickinson must start by the end of the year or risk losing funding and the president of the university where it’s located said it will be done and also that he’s in favor of the splitting up of the library and a museum in Medora as it’s “the best of two worlds.”

The Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library Foundation made the decision on the two sites at a meeting last month in Minneapolis.

It’s been a lot of time and talk, but now that the decision has been made and plans are underway to start building the library, Dickinson State University’s President Thomas Mitzel spoke about the vision for the library and how it will affect the university.

“One of the most important factors that we left the board meeting in Minneapolis with was that we were going forward as one project and two different sites. It’s not that uncharacteristic,” Mitzel said. “The Gerald Ford Presidential Library has two different sites … the intellectual piece and the museum piece.”

For about a year, Dickinson had been the only proposed home for the library and museum. However, recent changes in the Foundation’s board sparked discussion about incorporating a historic Medora location into the project’s plans.

Now the project is even larger than originally planned, with a price tag speculated at close to $150 million, and a library that needs to be built as soon as possible.

Materials put out by the Foundation prior to their meeting in March suggested that the library would be a 24,000-square-foot facility featuring an auditorium, office space and a timeline that would see construction beginning by November of 2018 and concluding in November 2019.

“I think the time was worth it (on making a decision on the two sites). It does put us in a bit of a crink, we do have to be vertical by the end of 2018 and I have no angst that we will meet that,” said Mitzel, who noted that the building committee has been meeting already trying to get the ball rolling.

“I think we really get the best of both worlds, it’s two buildings, one project,” he said.

Mitzel said that they don’t have any design plans to show at the moment, but that due to the library’s purpose as an intellectual and learning center, it won’t be too complicated or difficult to build.

Mitzel was hesitant to give too many specifics about the library’s interactive elements, but said there will be some.

“I don’t want to speak for everybody on the committee … but I would assume that yes, we would have interactive areas where people can go in and read about the workings of Theodore Roosevelt,” Mitzel said. “We may have areas for exhibits … that we can switch out every few months or so, to keep it vibrant.”

It will be important, Mitzel said, that the two buildings link to each other in meaningful ways to capture dual aspects of Roosevelt’s character- his love of the outdoors and his intellectual gigantism.

“We want to create an experience that ties the two of them together very closely, so that … you’ll want to see both,” Mitzel said. “If you’re more an outdoors, hiking person you may start in Medora … if you are more the intellectual type you may start here and then wander your way to Medora, but we really do hope it becomes one entity in people’s minds.”

While the library will now be hosted on DSU land, it is not a DSU-owned building—and while Mitzel stressed that point, he said that they still intend for students to use the facility.

“We’ve discussed this to a great extent, it is first and foremost a presidential library. It is not a DSU building, it is a presidential library,” Mitzel said. “With that, however, to have an international digital archive on campus and not to take advantage of that, we would be remiss. We’d be letting our students down. My dream is to have our students doing actual research in the presidential papers research project in some manner.”

“The feedback I’ve gotten … has been quite positive. I think for the community to understand that this building, with its intellectual slant, is going to reach out to education at every level, beginning K-12 and beyond and before,” Mitzel said. “That we’re really here to make the community … a large part of what we’re doing, it’s not just going to be an isolated building.”

Mitzel said he encounters many who assume that the popular Roosevelt, who was both a statesman and explorer, already had his own library. But he doesn’t—and to build it in North Dakota means something, Mitzel said.

“For us to have that chance to build that monument for our 26th president here in North Dakota, where in his own words had it not been for his years in North Dakota he would not have become president, I think that’s good for everybody,” Mitzel said. “Having the intellectual portion of it centered on the DSU campus gives everybody an opportunity to do so much.”

Source